The Paleo- Hebrew Alphabet The Complete Scientific Research

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

This is the main body of work connected to my Synoptic Index. Observations with Paleo-Greek, Ancient Egyptian, and Chinese confirm Paleo-Hebrew was not originally connected with Mesopotamian, but was a later influence from which we get the Acronym Theory and a connection to Proto-Sinaitic.

Related papers

Review of Biblical Literature, 2018

For about 150 years, scholars have attempted to identify the language of the world’s first alphabetic script, and to translate some of the inscriptions that use it. Until now, their attempts have accomplished little more than identifying most of the pictographic letters and translating a few of the Semitic words. With the publication of The World’s Oldest Alphabet, a new day has dawned. All of the disputed letters have been resolved, while the language has been identified conclusively as Hebrew, allowing for the translation of 16 inscriptions that date from 1842–1446 BC. These inscriptions expressly name 3 biblical figures and greatly illuminate the earliest Israelite history in a way that no other book has achieved, apart from the Bible.

Writing is one of the most important cultural marks of the Israelites. The Scriptures have accompanied the Israelites since the beginning of their nation-building at Mount Sinai. The Ten Commandments were written in Ancient Hebrew Alphabet. In Babylonia, the Israelites wrote their Tanakh in Aramaic characters. One must therefore ask why they left so little written material in Asia that would clearly identify them as Israelites, i.e. one would expect more Hebrew or Aramaic written monuments in Asia. In this paper, we will search for Israelites’ traces in written monuments of Eurasia.

Scientific enterprise is a part and parcel of the contemporaneous to it general human cultural and, even more general, existential endeavor.

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 2010

Evolution from Paleo Hebrew of the Baals to Jewish script

Joseph Biddulph, 2020

An attempt to clear away the clutter provided by the textual criticism of the Hebrew texts and to establish the linguistics of such a reconstruction. The stress on the importance of African linguistics is accompanied with literary-aesthetic ideas from the Sanskrit literary tradition which might be used to establish the integrity and dating of the Bible record.

This thesis will explain how the Hebrew alphabet was developed via numerics: i.e. the multiplication tables and the MATRIX OF WISDOM. Inherent in the structure of the Hebrew Alphabet in the mirror-imaging paradigm, which allows God to make Adam (humanity) into his own image. This same mirror-imaging paradigm is the core principle behind Michelangelo frescoing the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. Additionally, this analysis illustrates how the Hebraic Coder is a symbol of the Kundalini Serpent.

The change from Egyptian hieroglyphs to ancient Hebrew via Phoenician: ancient Mystery traditons

Rethinking Israel: Studies in the History and Archaeology of Ancient Israel in Honor of Israel Finkelstein, 2017

On 10 April 2017, ASOR's The Ancient Near East Today published an article I wrote, entitled, "Hebrew as the Language behind the World's First Alphabet?" On 14 April 2017, Alan Millard published a highly critical review of my ASOR article, which I addressed to non-specialist readers. In this responsive paper, I address each of Millard's criticisms cogently.

The article deals with the chronology and geographic distribution of the Late Bronze II to late Iron IIA alphabetic inscriptions found in the Levant, ca. 1300-800 B.C.E., with an emphasis on the archaeological context. It traces the expansion of the alphabet from its core area in the Shephelah in the Late Bronze age to the rest of the Levant starting in the early Iron IIA, ca. 900 B.C.E., and the parallel development of the alphabet away from Proto-Canaanite. Recent discoveries of stratified early alphabetic inscriptions at Tel Zayit, Tell eṡ-Ṡafi, Beth-shemesh, Tel Rehov and Khirbet Qeiyafa 1 have in some ways revolutionized our knowledge of the early alphabet in Israel, and by association also in the rest of the Levant. At issue are the Proto-Canaanite inscriptions of the Late Bronze II-III to early Iron IIA, and their earliest more developed descendants of early Iron IIA to early Iron IIB. 2 Before the discoveries just mentioned, there were very few inscriptions of Iron I and early Iron IIA from reliable archaeological contexts. 3 A fresh look at the alphabet during this period is also warranted considering recent progress in the study of the relative and absolute chronology of the Late Bronze II-III and the Iron Age. The spatial and temporal distribution of the inscriptions in question illuminates the spread of the alphabet before the

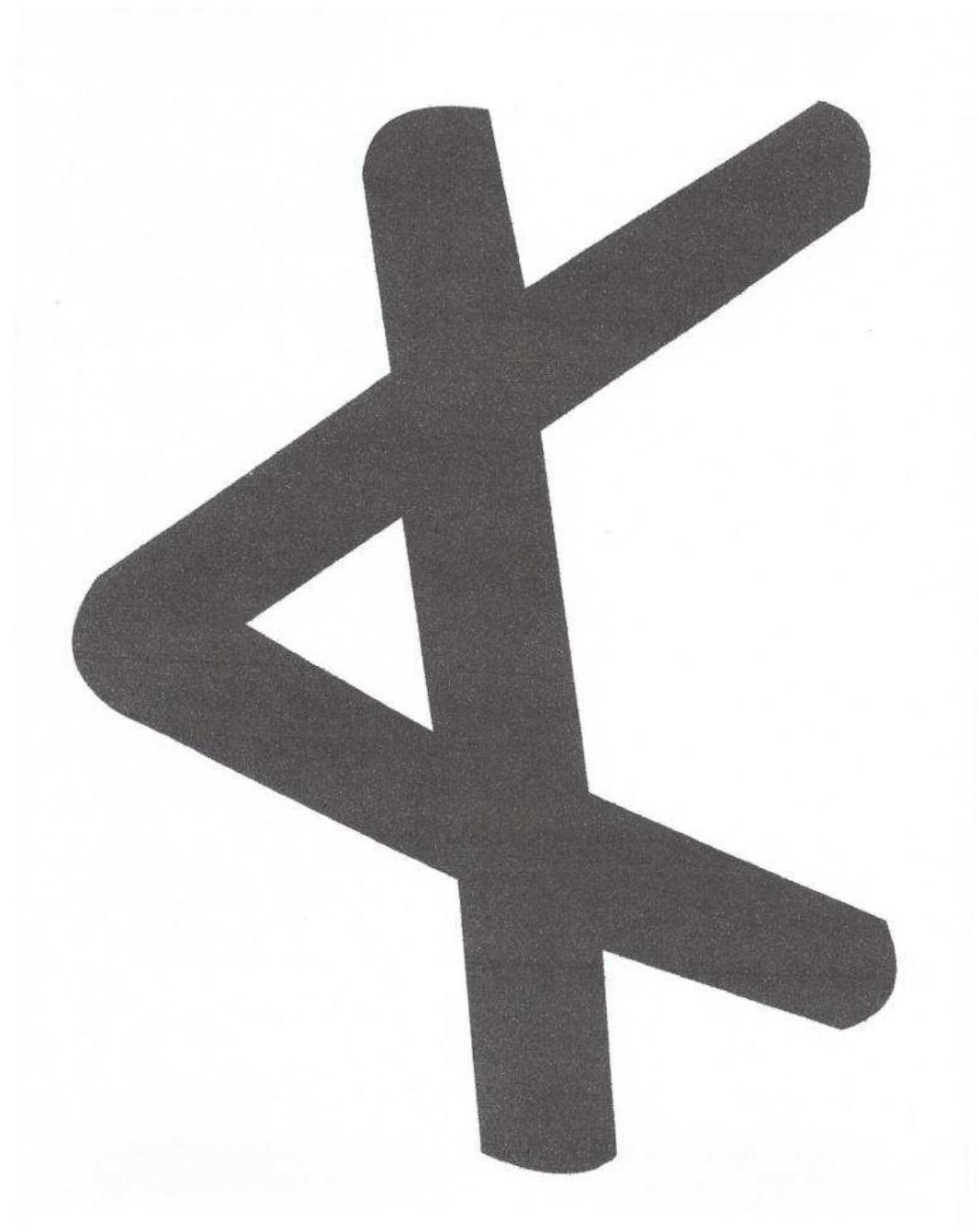

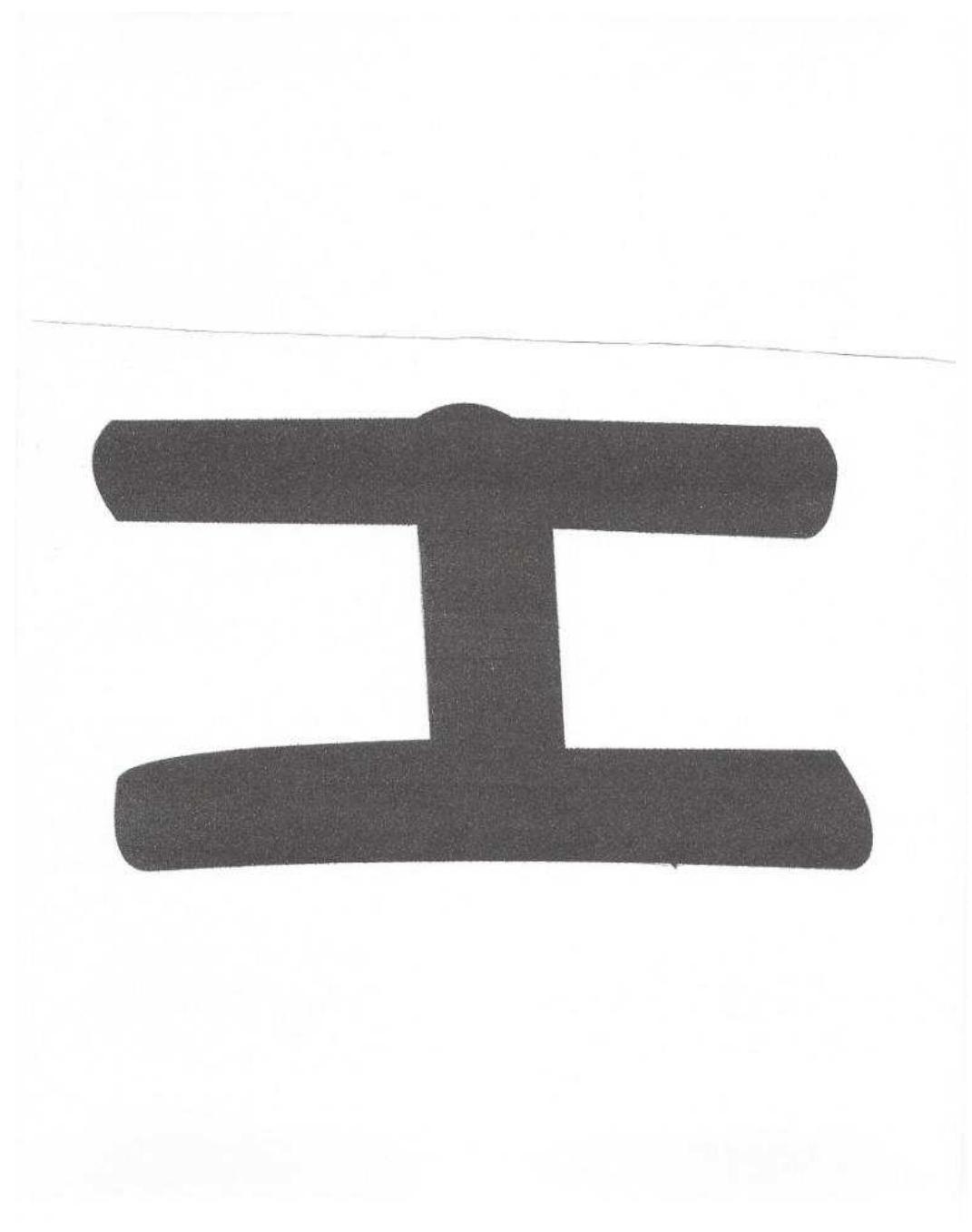

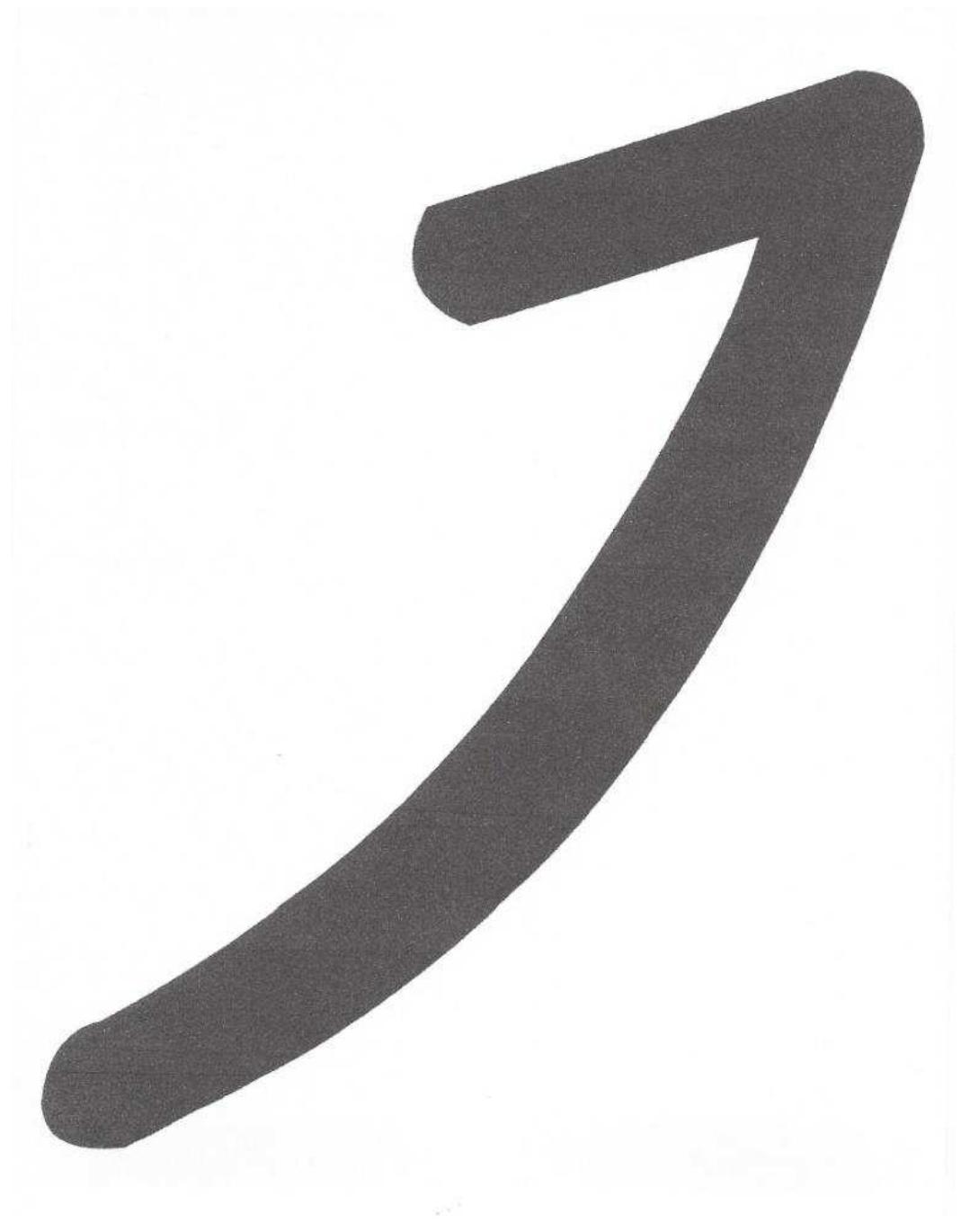

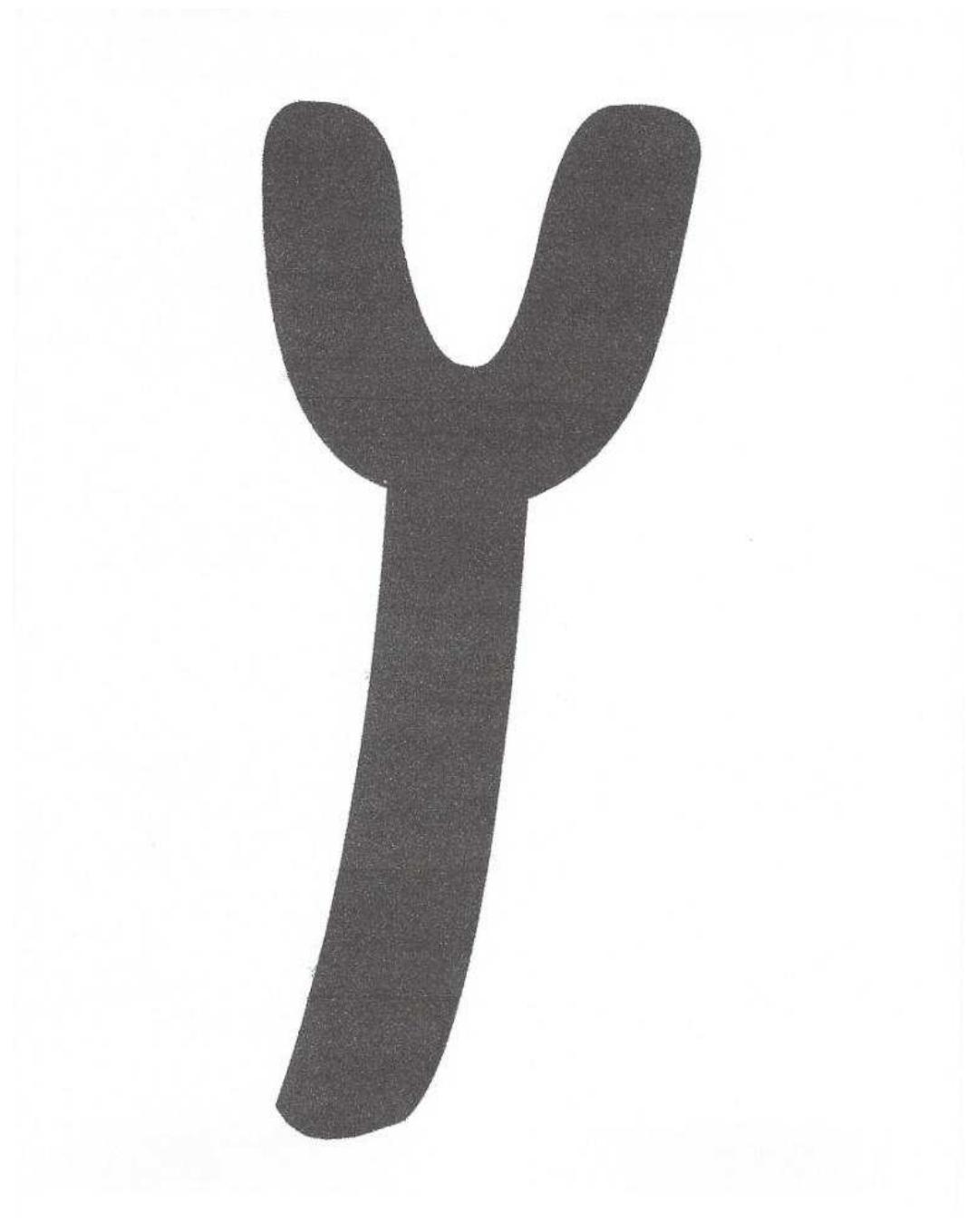

The first alphabet in the world was invented at the dawn of the second millennium BCE by Canaanite miners in the Sinai Desert. This alphabet is the origin of all the scripts we still use today in Hebrew, Arabic, English, Russian, and most modern languages of the western world. The alphabetical system was invented only once, and all the alphabetical scripts we know today developed from this first system. From the end of the fourth millennium BCE up to the invention of the alphabet, Ancient Near Eastern scribes used scripts that comprised hundreds of signs: cuneiform script was used in Mesopotamia, and hieroglyphic script-a pictorial script-in Egypt. A script is a set system of signs that is capable of transmitting linguistic messages. No clear evidence of the use of scripts dating prior to the second millennium BCE has been found outside the Ancient Near East. In order to read and write the pre-alphabetic scripts of the Ancient Near East one had to memorize hundreds of characters. Furthermore, the manner in which these characters guided their readers from sign to word was often tortuous. Some Egyptian words were represented by hieroglyphs that depicted the word's meaning. For instance, the symbol for the word "ox" was , and the word for dais, or platform, was depicted thus:. But when a word's meaning could not be accurately conveyed by a single picture, as is the case for most words in any language, a series of symbols was enlisted for the task. However, these pictures no longer served their original function, as they now represented only a sound or a combination of sounds. To illustrate, if "exodus" were an Egyptian word, it might have been depicted as "ox-dais" − − with the hieroglyphic characters functioning as a chain of consonants, since vowels were not represented in Egyptian script. To these two signs, the Egyptian scribe would have appended at least one more sign, which in our fictional example might have been. This is an unpronounced sign, which was not part of the phonetic chain comprising the word. Instead, it functioned as a classifier that indicated the semantic category of the word, in this case signifying "movement." Our word would thus have been written , but today we would write it with an asterisk to denote that this is a modern construct and not an authentic Egyptian word (*). Unlike many modern languages, Egyptian did not have a set writing direction. The word * (from left to right) could just as well have been written * (from right to left). The only rule was that texts were read "into" the symbols, meaning each hieroglyph faced the beginning of the line. This seems somewhat counterintuitive to modern readers (as it likely seemed to many ancient readers, as well). Further complicating the Egyptian script, the hieroglyph depicting an ox () could function in an additional way: as an unpronounced semantic classifier denoting the category "cattle" following nouns such as cow or calf. A single symbol could thus have three distinct roles in the Egyptian writing system: as an ideogram of the depicted object; as a phonogram representing the sound or sounds of the word it depicted; and as an unpronounced classifier. The new writing system invented by Canaanite workers in the Sinai Desert was a remarkable stroke of genius. Instead of using hundreds of signs, there were now fewer than thirty to memorize, and these served to indicate single sounds, and sounds only. This small number of characters sufficed to represent each and every word in the language. Furthermore, instead of applying a complex set of reading rules, the alphabet offered one, fixed method of reading.

Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, 2012

Related topics

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Travis Wayne Goodsell

Travis Wayne Goodsell