History of Baptismal fonts

2021, History of Baptismal fonts

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

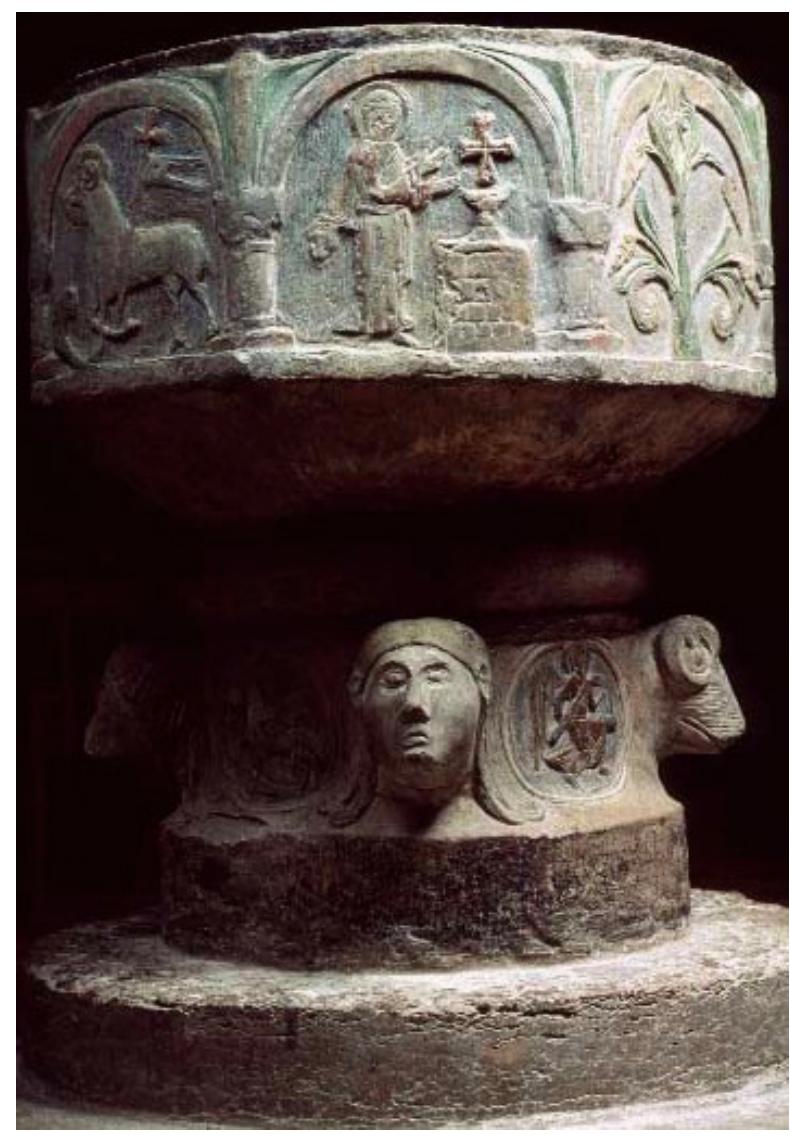

History of Baptismal fonts The first real Baptismal fonts we find in Gotland. It is the font in Etelhem church that is dedicated to Hægwaldr. He works in sandstone. Hegwaldr’s art is the gateway between the old and new Gotlandic art. His style is fundamental for the Gotlandic baptis- mal fonts. It is not impossible that he has had a fundamental role as an architect. The earliest fonts were made in sandstone. Only a few have been exported. Later with Calcarius the fonts are made in limestone. Of these only two are found in Gotland. More than 1500 have been exported from Gotland and we find them all around the Baltic Sea. References to figures is in the book: The Gotlandic Merchant Republic and its Medieval churches

Key takeaways

- Roosval in 'Die Steinmeister Gottlands' groups the Gotlandic sandstone Romanesque baptismal font workshops into style groups; Hegwaldr, Majestatis, Semi-Byzantios, Byzantios, Sigrafr.

- To begin with, it can be concluded that the font has basically the same structure as most Romanesque Gotlandic fonts.

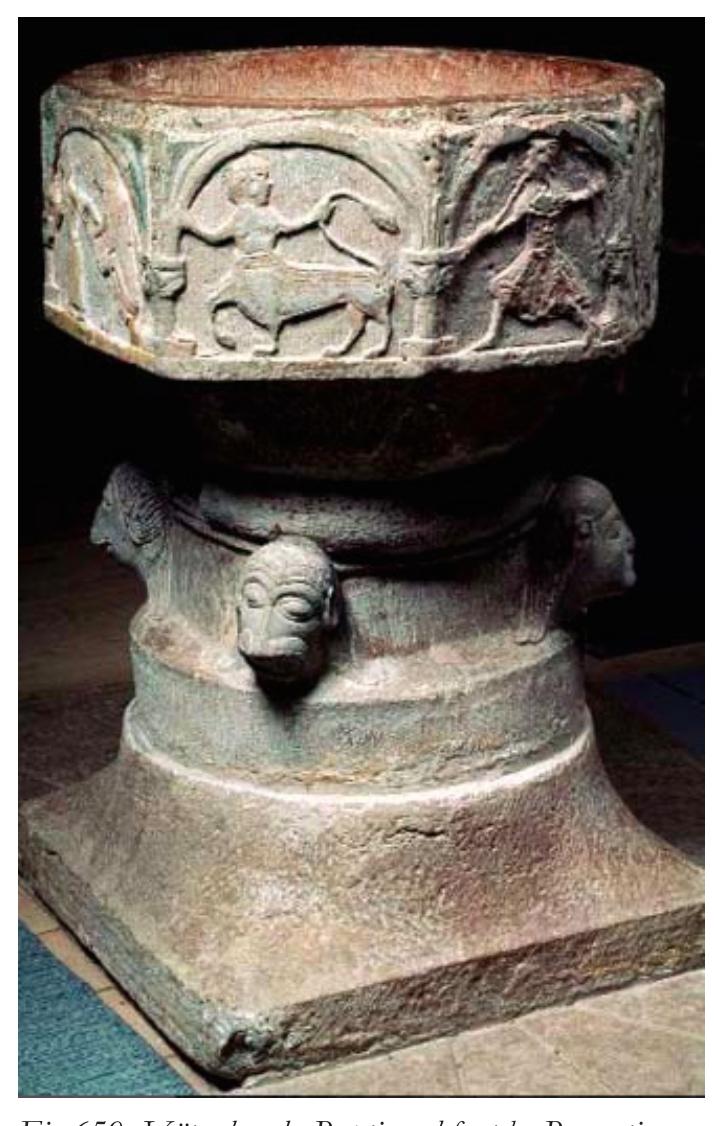

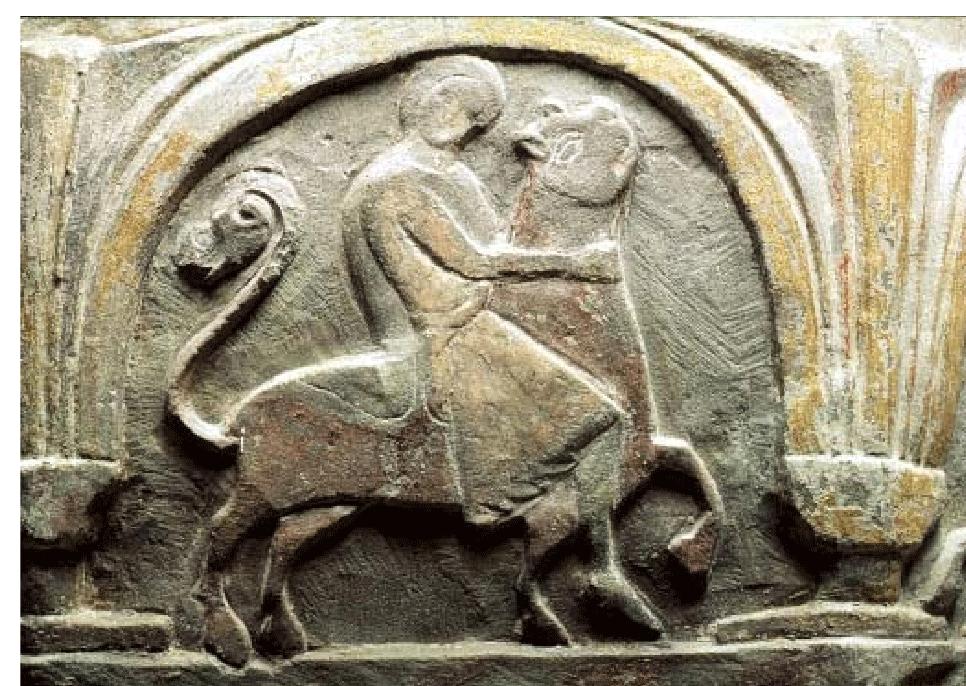

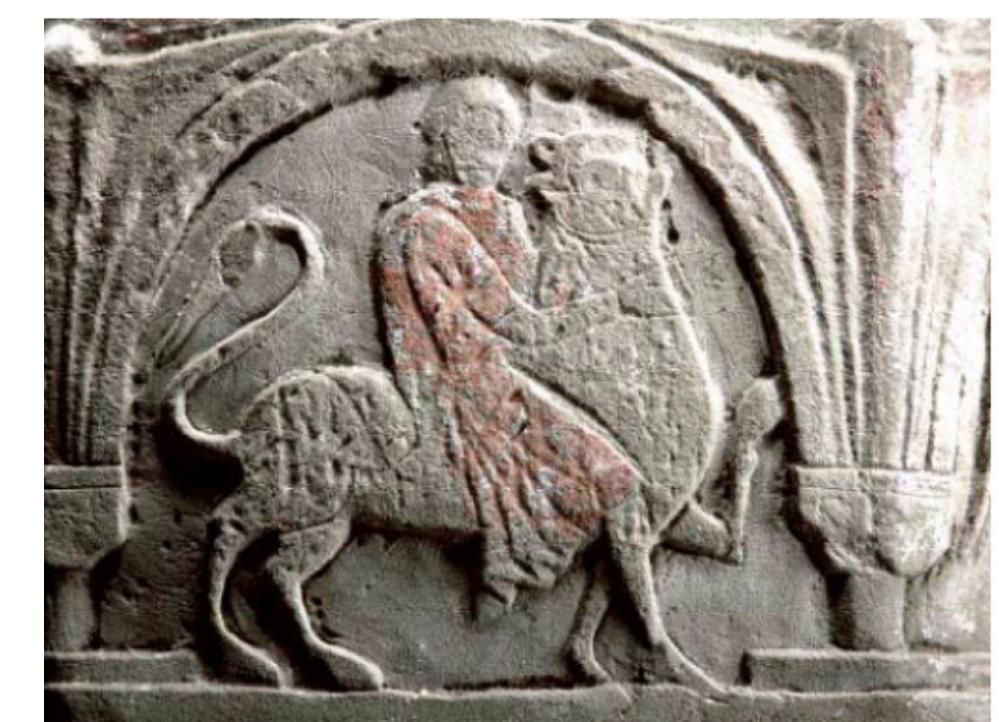

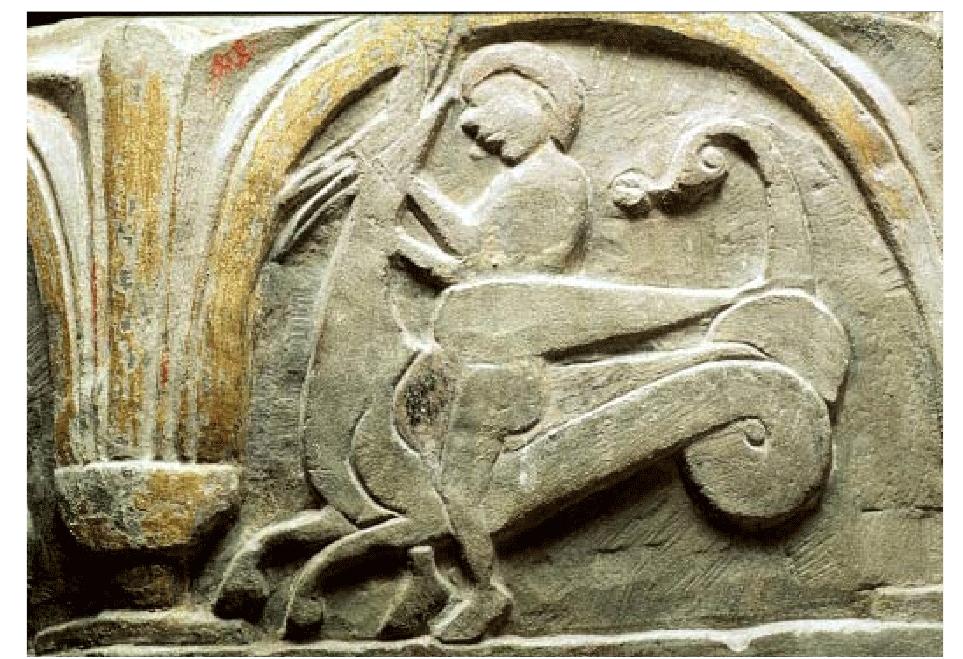

- It is partly a man with the head more beautiful and delicate styled than any of the other fonts by the Gotlandic masters, a ram, and two lions, or rather, a lion and a panther, who, however, is not as nice as the lions on Byzantios' fonts, where the baboon-like noses are pointing downwards and never have anything in the gap.

- Firstly it has an arcade division on the cup and that the foot of the font has protruding animal heads similar to those found on fonts in the earlier groups, but lacks on the other fonts within the Sigrafr group.

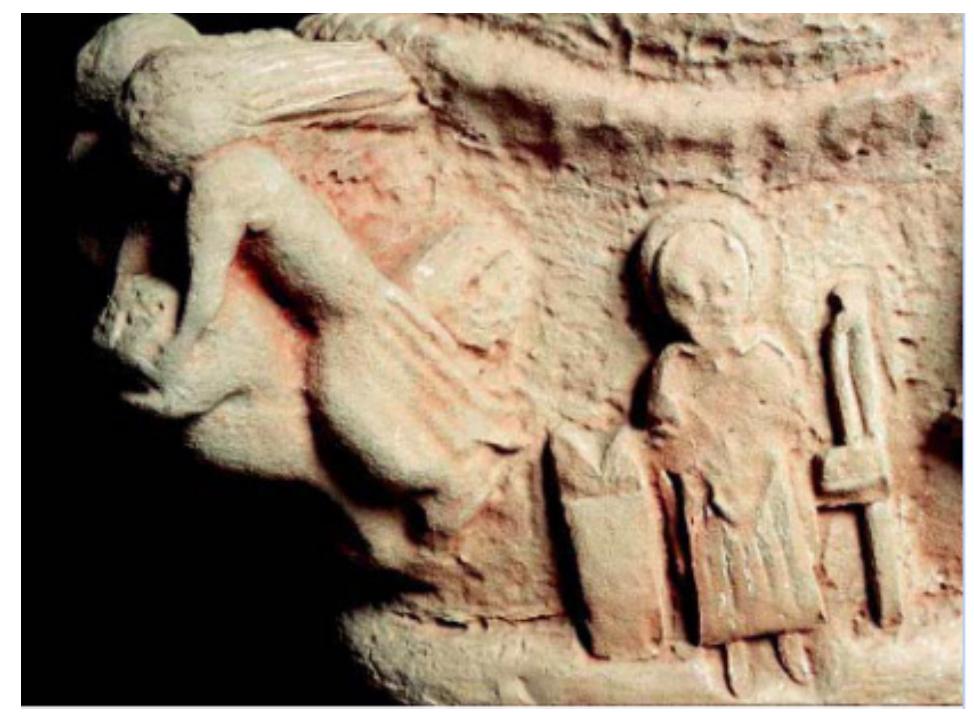

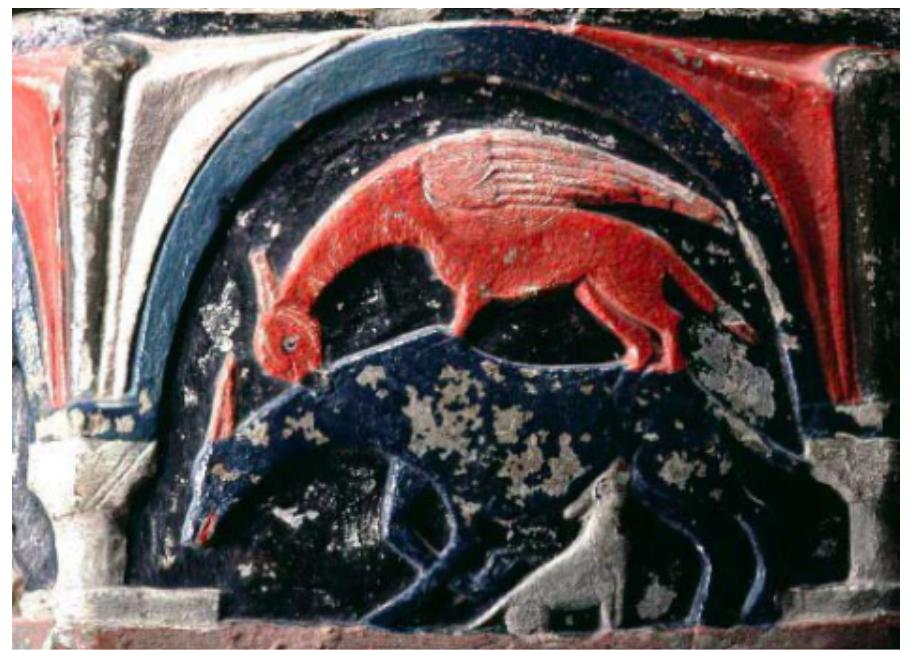

- When the Gotlandic stone master, who Roosval has given the anonymous master namne Byzantios, in the 1000s cut his baptismal fonts and the friezes on Vänge Romanesque church, he chose to adorn the cups and walls with representations of fable animals and figurative scenes, which apparently has a symbolic meaning.

Related papers

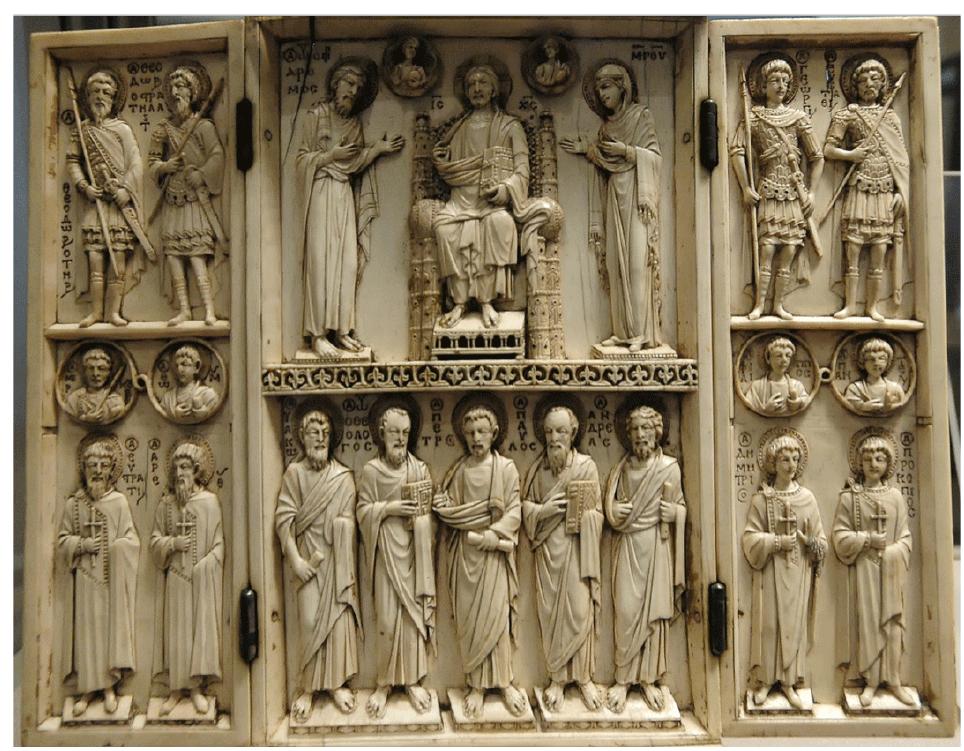

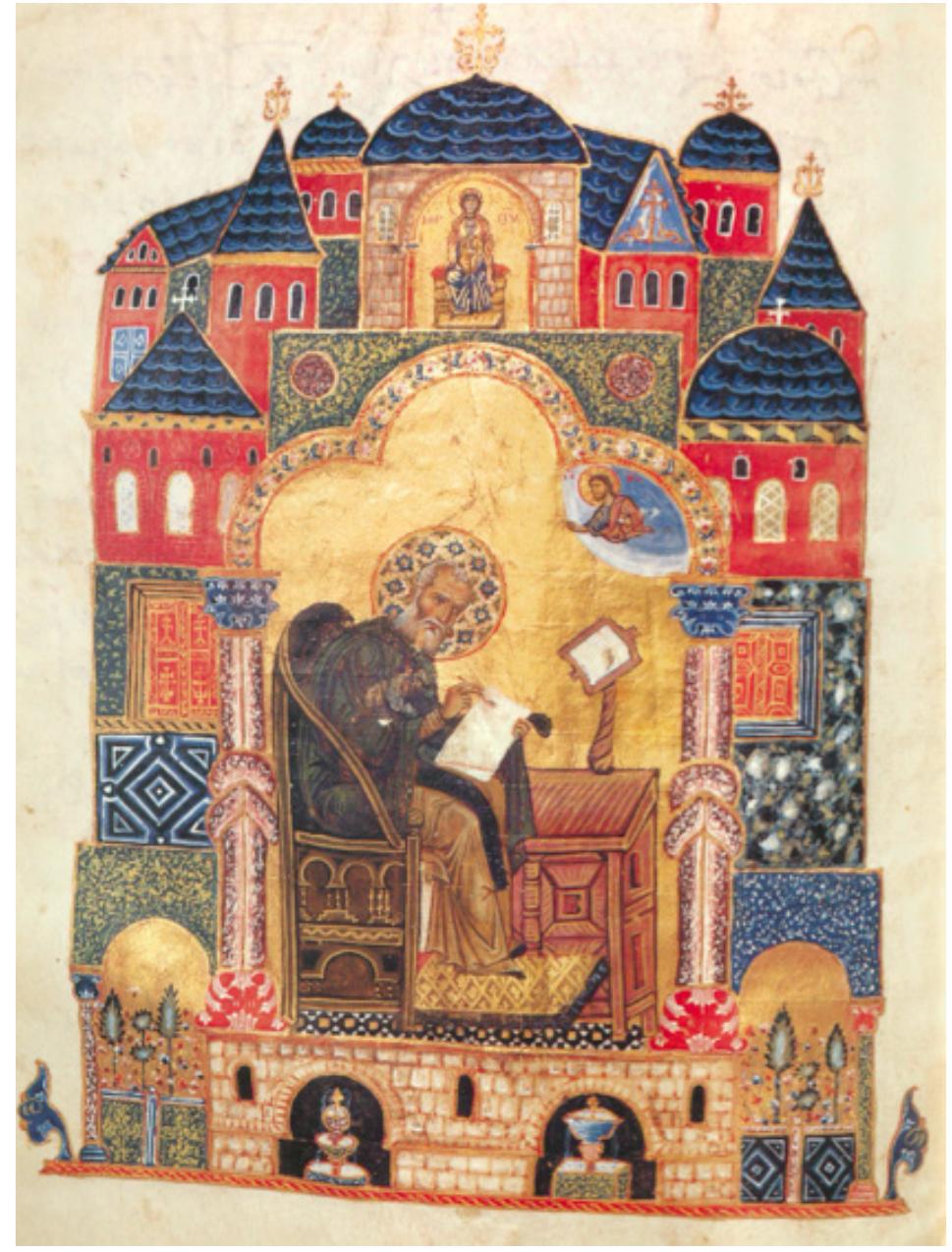

We don’t know whether the Gotlandic sandstone Baptismal fonts already were made for the wooden churches in the 900s or only were made when the stone chuch that replaced the wooden church was inaugurated. However Haegwaldr’s early works definitely belong to the 900s. There is no question that the early Gotlandic Romanesque churches were heavily influenced by the Macedonian Renaissance art. The three Sacraments of Initiation are Baptism, Chrismation, and Divine Eucharist. The prototype for the Gotlandic Baptismal fonts could very well be the Byzantine Chalices, which is the second of the Sacraments, and use the Chalise as prototype for Baptismal fonts, which is the first sacrament, adapted to the Gotlandic school of art. In Eastern Christianity chalices will often have icons enameled or engraved on them, as well as a cross. In Christian tradition the Holy Chalice is the vessel which Jesus used at the Last Supper to serve the wine. New Testament texts make no mention of the cup except within the context of the Last Supper and give no significance whatever to the object itself. Herbert Thurston in the Catholic Encyclopedia 1908 concluded that “No reliable tradition has been preserved to us regarding the vessel used by Christ at the Last Supper. In the sixth and seventh centuries pilgrims to Jerusalem were led to believe that the actual chalice was still venerated in the church of the Holy Sepulchre, having within it the sponge which was presented to Our Saviour on Calvary.” Several surviving standing cups of precious materials are identified in local traditions as the Chalice. The foot of the Baptismal font shows an interesting development. The oldest Gotlandic baptismal font lodges given their anonymous names by Roosval are: Hegwaldr, Majestatis, Semi-Byzantios, Byzantios and Sigrafr. They have built the fonts in the same manner, cup, a low cylinder which is conically sloping downwards and on the foot four diametrically protruding heads adjacent to each other. The fonts are well cut and at the same time they form the largest contrasts in the Gotlandic art of sculpture. In almost every point is the ornamentation of the one the diametric contrast to the other. This gives immediately a remarkably wide horizon for the Gotlandic art, and unites the principal amount of problems in itself, that the Gotlandic history of sculpture can offer.

a review of sites

2024

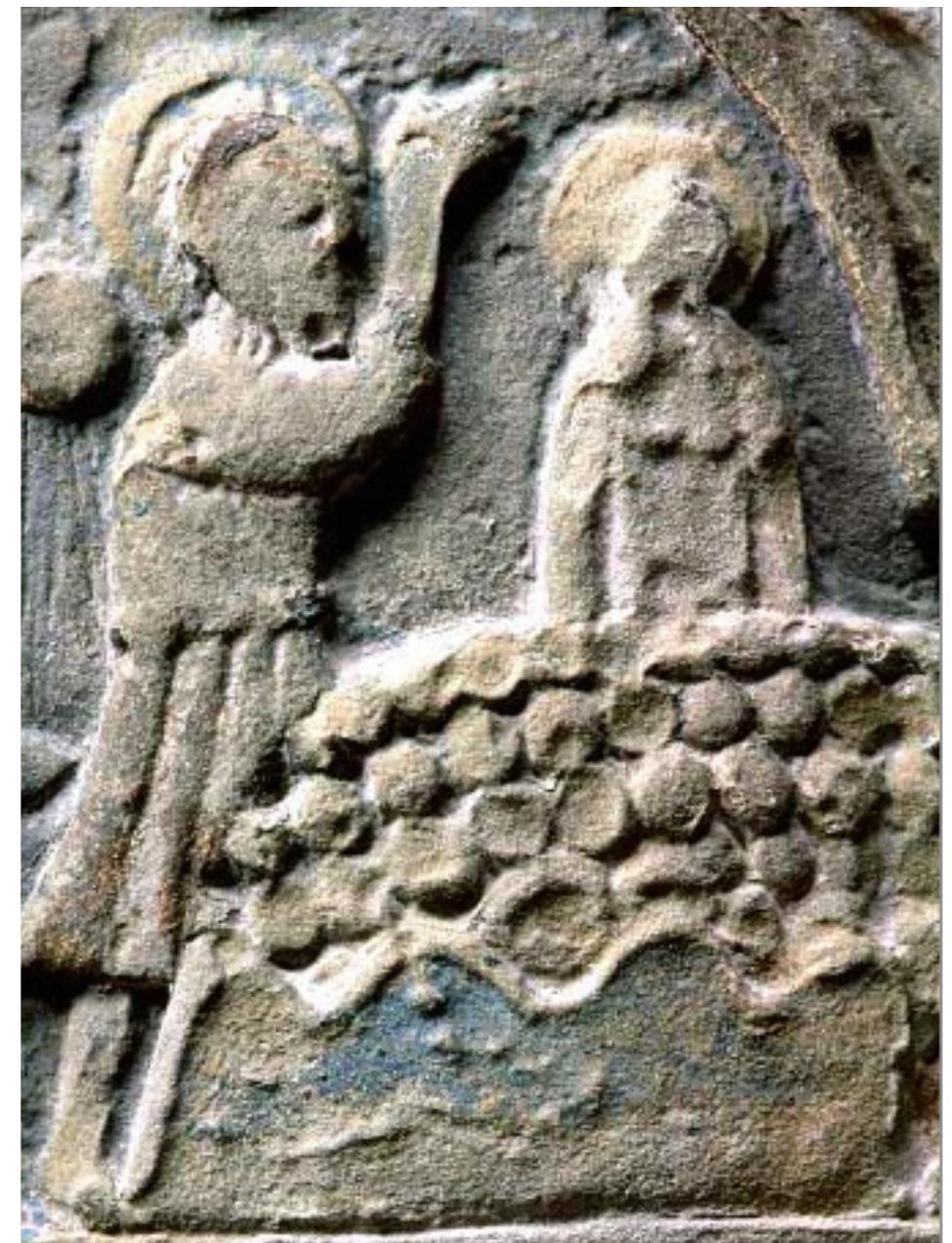

Open Access Book: This is the first comprehensive, interdisciplinary analysis to demonstrate that the representation of Infancy cycles on twelfth-and-thirteenth-century baptismal fonts was primarily a northern predilection in the Latin West directly influenced by the contemporary military campaigns. The Infantia Christi Corpus, a collection of approximately one-hundred-and-fifty fonts, verifies how the Danish and Gotland workshops modified and augmented biblical history to reflect the prevailing crusader ideology and rhetoric that dominated life during the Valdemarian era in the Baltic region. The artisans constructed the pictorial programs according to the readings of the Mass for the feast days in the seasons of Advent, Christmas and Epiphanytide. The political ambitions of the northern leaders and the Church to create a Land of St. Peter in the Baltic region strategically influenced the integration of Holy Land motifs, warrior saints, militia Christi and martyrdom in the Infancy cycles to justify the escalating northern conquests. Neither before nor after, in the history of baptismal fonts, have so many been ornamented with the Infancy cycle in elaborate pictorial programs. A brief revival of elaborate Infancy cycles occurs on the fourteenth and fifteenth century fonts commissioned for sites previously located in the Christian borderlands east of the Elbe River with the rise of the Baltic military orders and the advancement of the Church authority. This extraordinary study integrates theological, liturgical, historical and political developments, broadening our understanding of what constituted northern crusader art in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Recent history of the piece Lead baptismal fonts: exceptional and scarcely preserved objects A workshop for a font. The Occitan lead baptismal fonts Brief history of the research Decorative models used by the workshop Other fonts attributed to the same workshop General characteristics of the workshop that manufactured the font Chronology Continuity through time Conclusions

The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 2003

It will not do, for example, to take the views of Gregory the Great, who lived in the late sixth century, and whose world was essentially European, as typifying the opinions of the fourth-century Roman popes in matters of art. And there is no indication of acquaintance with the various current reinterpretations of historical periods such as the Renaissance. But it is the systematic discussion which is the most unexpected. Despite the focus on reformed theology, there is no treatment of the pioneering work done in the art field by Paul Tillich, and yet Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who never made aesthetics or art a major consideration in his work, is given a whole chapter, in a treatment which must be regarded as highly speculative. The most helpful and interesting part of this book is the study of and analysis of South African art and society, which is a new and original and a very welcome addition to the subject. MARY CHARLES-MURRAY UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Hagiographies, III : International history of the Latin and vernacular hagiographical literature in the west from its origins to 1550. Edited by Guy Philippart. (Corpus Christianorum.

Written for the course 'The Church and the Arts' at Boston University, this paper uses an analysis of the design and location of six recent baptismal font installations at American Lutheran churches to explore the theological, liturgical, and practical issues faced by these congregations in affirming their sacramental heritage and fulfilling their mission of welcoming people of all ages into the life of the Church.

Architectus, 2023

The article discusses the study of the baptismal font located next to the presbytery of Saint Nicholas parish church in Grudziądz. The aim of the research conducted in 2023 was to verify current views on its centuries-old history. Our study presents the history of the object, its artistic provenance, iconography and ideological content. Based on the research, it was found that the late Romanesque baptismal bowl is an original work of Gotland provenance, dating back to the 2nd half of the 14th century. Its Gotland origin is evidenced by formal, compositional and iconographic analogies connecting its creator with the style of Gotland workshops known as the so-called Fröjel Group that was active in Gotland and southern Scandinavia around the mid-14th century. The decisive argument for the origin of the baptismal font from Gotland was the petrographic examination of its stone carried out in July 2023, which showed that it was made of Gotland limestone found in the Hoburgen deposits. This work should therefore be treated as an import from Gotland. The article also emphasizes that in order to illustrate the theological message, the creator of the baptismal font – in accordance with the tradition present in his artistic environment – used symbolic representations of animals, the iconography of which and the dramaturgy of actions involving them were taken from the medieval bestiary – Physiologus. The beasts shown on the baptismal font, exorcised by baptism, walk in a row towards Christ symbolized by a lion. // W artykule zostały omówione badania chrzcielnicy ustawionej przy prezbiterium fary pw. św. Mikołaja w Grudziądzu. Celem badań prowadzonych w 2023 r. była weryfikacja dotychczasowych poglądów na temat jej wielowiekowej historii. W pracy została zaprezentowana historia obiektu, jego proweniencja artystyczna, ikonografia i treści ideowe. Na podstawie badań stwierdzono, że późnoromańska czasza chrzcielnicy jest oryginalnym dziełem gotlandzkiej proweniencji, datowanym na 2. połowę XIV w. Za jej gotlandzkim pochodzeniem świadczą analogie formalne i kompozycyjno-ikonograficzne łączące jej twórcę ze stylistyką warsztatów gotlandzkich znanych jako tzw. Grupa Fröjel, czynnych na Gotlandii i w południowej Skandynawii około połowy XIV w. Decydującym argumentem o pochodzeniu chrzcielnicy z Gotlandii stało się badanie petrograficzne jej kamienia w lipcu 2023 r., które wykazało, że została wykonana z gotlandzkiego wapienia występującego w złożach Hoburgen. Należy zatem traktować to dzieło jako import z Gotlandii. W artykule podkreślono także, że w celu zilustrowania teologicznego przesłania twórca chrzcielnicy – zgodnie z tradycją obecną w jego środowisku artystycznym – sięgnął po symboliczne przedstawienia zwierząt, których ikonografię oraz dramaturgię akcji z ich udziałem zaczerpnął ze średniowiecznego bestiariusza – Fizjologa (Physiologus). Ukazane na czaszy chrzcielnicy bestie, egzorcyzmowane przez chrzest, idą w szeregu ku Chrystusowi symbolizowanemu przez lwa.

Alyce A. Jordan and Kay Brainerd Slocum, eds.,Thomas Becket in the Middle Ages and Beyond: The Uses and Reception of a Celebrity Saint ( Boydell and Brewer), 2025

Quote from INTRODUCTION by Kay Brainerd Slocum: “An overt use of the Becket cult for political and religious ends occurred in medieval Denmark, as Harriet Sonne de Torrens documents in her essay. She analyses the imagery on two unique baptismal fonts that depict the martyrdom of Becket within the context of the escalating power of the northern Church and the Baltic Crusades, specifically in relation to the role of Bernard of Clairvaux and the Cistercian order. Veneration of St Thomas in Denmark and the Baltic regions was used to consolidate and reinforce the sanctity and authority of the Church. The spread of Becket’s cult was, in part, a result of the patronage of the daughters of Henry II, and some scholars have credited members of the royal Valdemarian dynasty with a similar role in medieval Denmark. While acknowledging the possibility, Sonne de Torrens complicates this attribution by elucidating evidence of anti-royal sentiment in the imagery found on the fonts. In medieval Denmark, the Canterbury saint was understood as a ‘notable martyr’, a miles Christi who died in the service of the Church. Moreover, the Baltic Crusades generated intense interest in warrior saints as part of the ecclesiastical propaganda that justified the campaigns to Christianise the pagan areas surrounding the Baltic Sea. Becket’s role in this conflict is established in a miracle recorded by William of Canterbury, which recounts Becket’s intervention in, and by extension endorsement of, the crusades to guarantee the Danish victory over the Wends.Becket’s engagement in the battle shifts the Danish victory from the agency of the Crown to that of the Church and attests to the strong interrelationship between the development of Becket’s cult and Cistercian influence in the Baltic Crusades, as part of the escalating power and sacred authority manifested by the Church in these newly Christianised regions.” (Images of Thomas Becket in the Middle Ages and Beyond: The Uses and Reception of a Celebrity Saint, pp. 13-14)

2016

Rezension zu: Pierre Colman & Berthe Lhoist-Colman: Les fonts baptismaux de Saint Barthélemy à Liège. Chef-d'oeuvre sans pareil et noeud de controverses (Académie Royale de Belgique, Mémoire de la Classe des Beaux-Arts, Collection in-8°, 3e série, Tome XIX); Bruxelles 2002; ISSN 0378-7923, ISBN 2-8031-0189-0; 341 pp., ill.

2012

offers some interesting burial evidence, much of it from the later Middle Ages, regarding the possibility that a number of children may not have received baptism before the age of two. Material evidence is unfortunately incomplete for the twelfth century.

ICO - Iconographisk Post, 2020

Since 1823 the consecration date of 1129 for the Church of St. Boniface inscribed on the Freckenhorst baptismal font from the imperial convent of St. Boniface (Westphalia, Germany) has continued to be considered, by some, the date for when the font was carved. For over two hundred years this precocious date has divided academic communities, despite the numerous and comprehensive counter arguments asserting that the font is a later twelfth century if not early thirteenth century vessel. This raises the question, “Why has there been such resistance to recognize this vessel as a later product of the prolific Westphalian stone industry?” This article reviews the historiography to uncover the roots of the ‘sanctified status’ that the Freckenhorst font acquired over the centuries from the post-Imperial period of Germany through the two World Wars. The literature reveals not only why the Freckenhorst font came to symbolize ‘Germanic ingenuity’ for German art historians but also the challenges and changes within the evolving discipline of art history and the scholarly networks that connected art historians in the first half of the twentieth century.

Studia Liturgica, 2006

There is a group of thirty-five octagonal baptismal fonts which were carved in stone on the eve of the Reformation in England bearing images of the seven sacraments. All but two are in Norfolk and Suffolk.' They were first described in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and have more recently been the subject of a major study by Ann Eljenholm Nichols." Nichols establishes the archaeological data for the fonts and locates them within a comprehensive survey of the iconography of the sacraments.' The fonts are particularly interesting because they witness to sacramental practice at a well-defined time and place: they were produced during a fifty-year period after the mid-1460s, though a couple of them were carved later, at the very last possible moment, in 1536 and 1544. One area of research which has been left underdeveloped is the contribution these panels make to our understanding of the celebration of the liturgy on the eve of the Reformation in England." Nichols has shown that the variety in the images indicates that the fonts were not produced in a workshop according to a standardized formula. In addition, the rather crude carving on a number of the fonts

This brief article is the first part of a planned multi-part project tentatively entitled "A Visit to the Church" (which is proceeding at a glacial pace). It looks at the history and spiritual significance of the holy water font.

Baptême et baptistères entre Antiquité tardive et Moyen Âge: Actes du colloque international qui s’est tenu à Paris, à Sorbonne Université, les 12-13 novembre 2020 (eds. Beatrice Caseau and Lucia-Maria Orlandi), 2023

My study, in addition to being the first relative chronology of baptismal fonts in Ethiopia, seeks to explain both their relative rarity after Late Antiquity, and their Medieval disappearance through the material and liturgical record. I argue baptismal fonts were exceptional after Late Antiquity. Their rare appearance is likely due to Ethiopian Christian preference for baptism in natural bodies of water, a practice justified both in the Apostolic Tradition (translated into Ge’ez in Late Antiquity), as well as biblical and early Christian precedents. By the late Middle Ages, the preference for baptism in natural bodies of water was recodified in canon law, both in the Ethiopic Sinodos and the Fetha Nagast (the law of kings), which outlined religious codes in Ethiopia (written in Arabic in the thirteenth century and translated into Ethiopic in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries respectively), which continued to justify natural water baptism instead of piscinas.

Ecclesia orans, 2022

Part 1 of this paper briefly describes Cgm 9509 of the Bavarian State Library (BSB), a previously unstudied manuscript containing a Catholic, vernacular baptismal rite from Reformation-era Germany. This research presents its context and provides the author’s transcription and translation of this rite. This increases our understanding of the usage of the vernacular in the liturgy in the Reformation era and presents the manuscript for further study. In the second part of this paper, the manuscript will be compared to a printed rite with which it is catalogued together in the BSB. The author begins to answer questions regarding the co-usage of these books and the genesis of the manuscript.

Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2014

Digital Photogrammetry has a distinct advantage over other 3D recording techniques in archaeology because of its scale independence; the same software can be used at both the object and the site-levels. We show that modern photogrammetric techniques were successfully employed to record a large, reconstructed marble Kantharos, an important part of the Baptistery adjacent to the Episcopal Basilica at Stobi. From this 3D model we can extract cross-sections that would otherwise not be attainable with an object so large using traditional techniques for ceramic profiling. Finally, we point to the utility of Digital Photogrammetry in providing assets for a virtual anastylosis of the Baptistery ahead of the planned physically anastylosis.

Collegium Medievale, 2022

In order for Roman alphabet inscriptions to be useful primary sources for historical, linguistic or other research, it is important that they are dated. Moreover, the user of these inscriptions should be able to judge the quality, i.e., the certainty, or uncertainty of the proposed dates. Several criteria for dating Roman alphabet inscriptions are presented, based on my cataloguing work in the project "Between Runes and Manuscripts". These are applied on Guðrun's gravestone from Hallvard's Cathedral in Oslo. Øystein Ekroll and Bent Lange have previously dated this gravestone to c. 1200, however, I argue that the inscription should be dated to the fourteenth century.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Tore Gannholm

Tore Gannholm