EXCAVATIONS AT MADINA DISTRICT ROHTAK, HARYANA, INDIA

2016, South Asian Archaeology Series 1

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

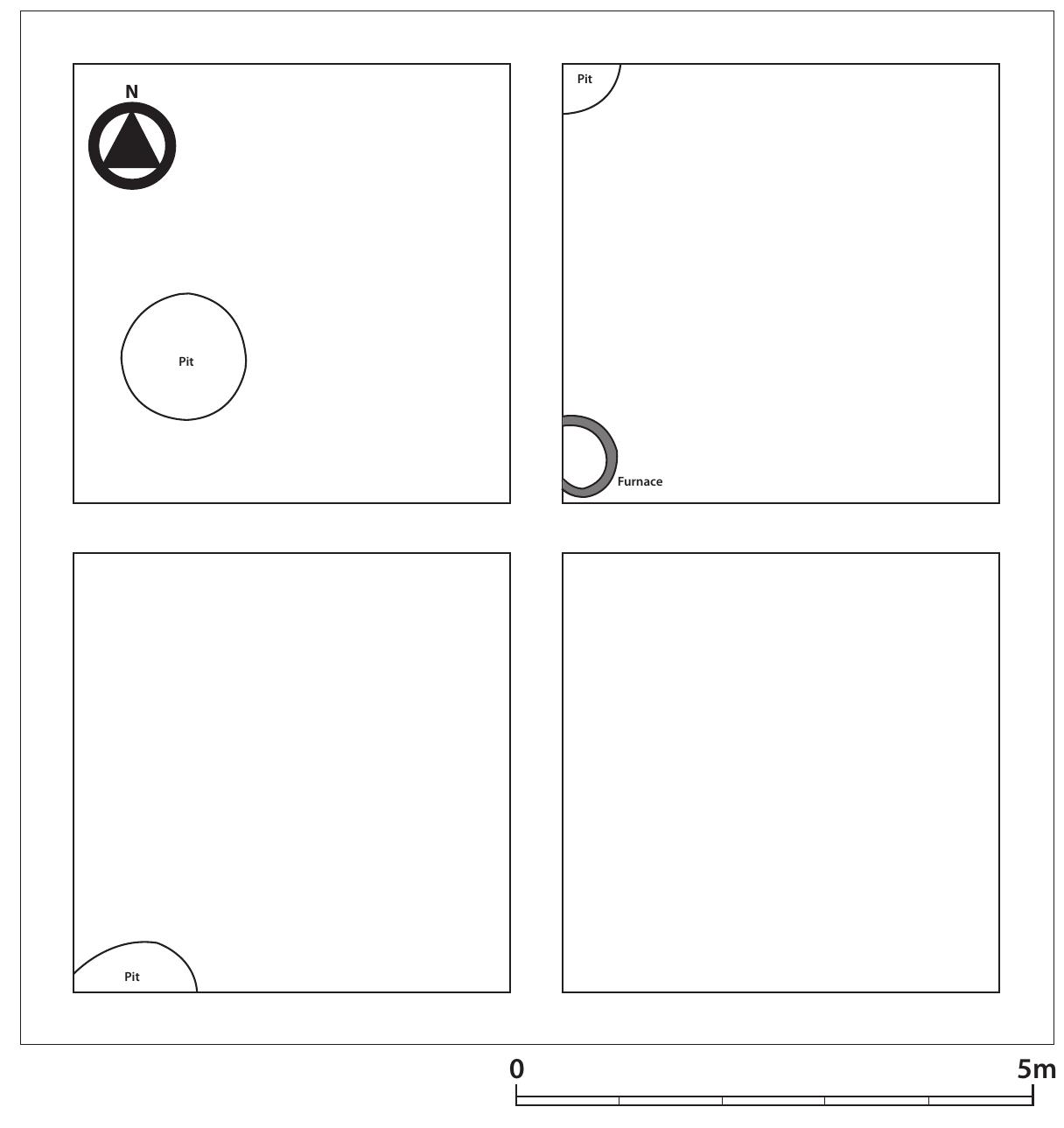

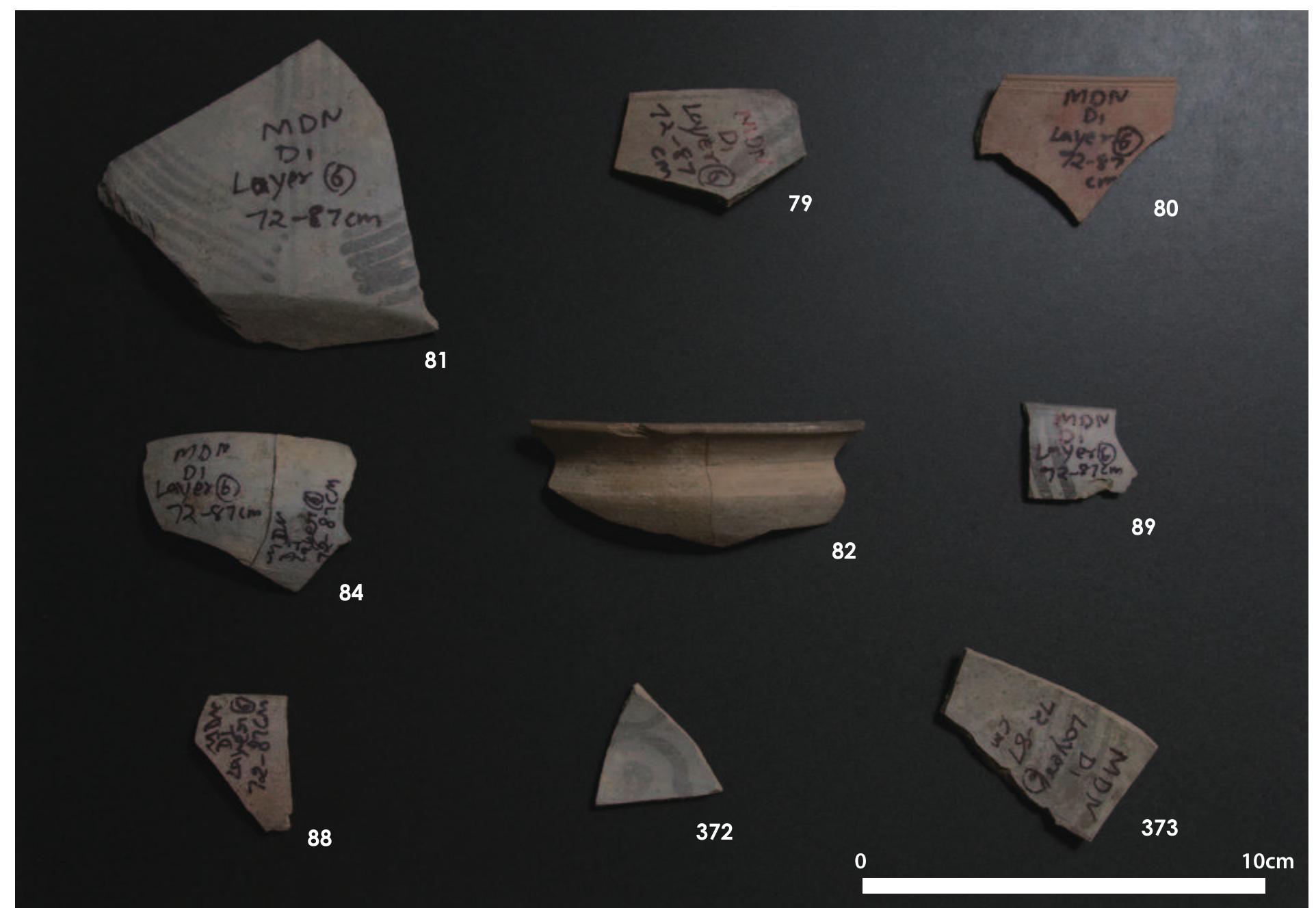

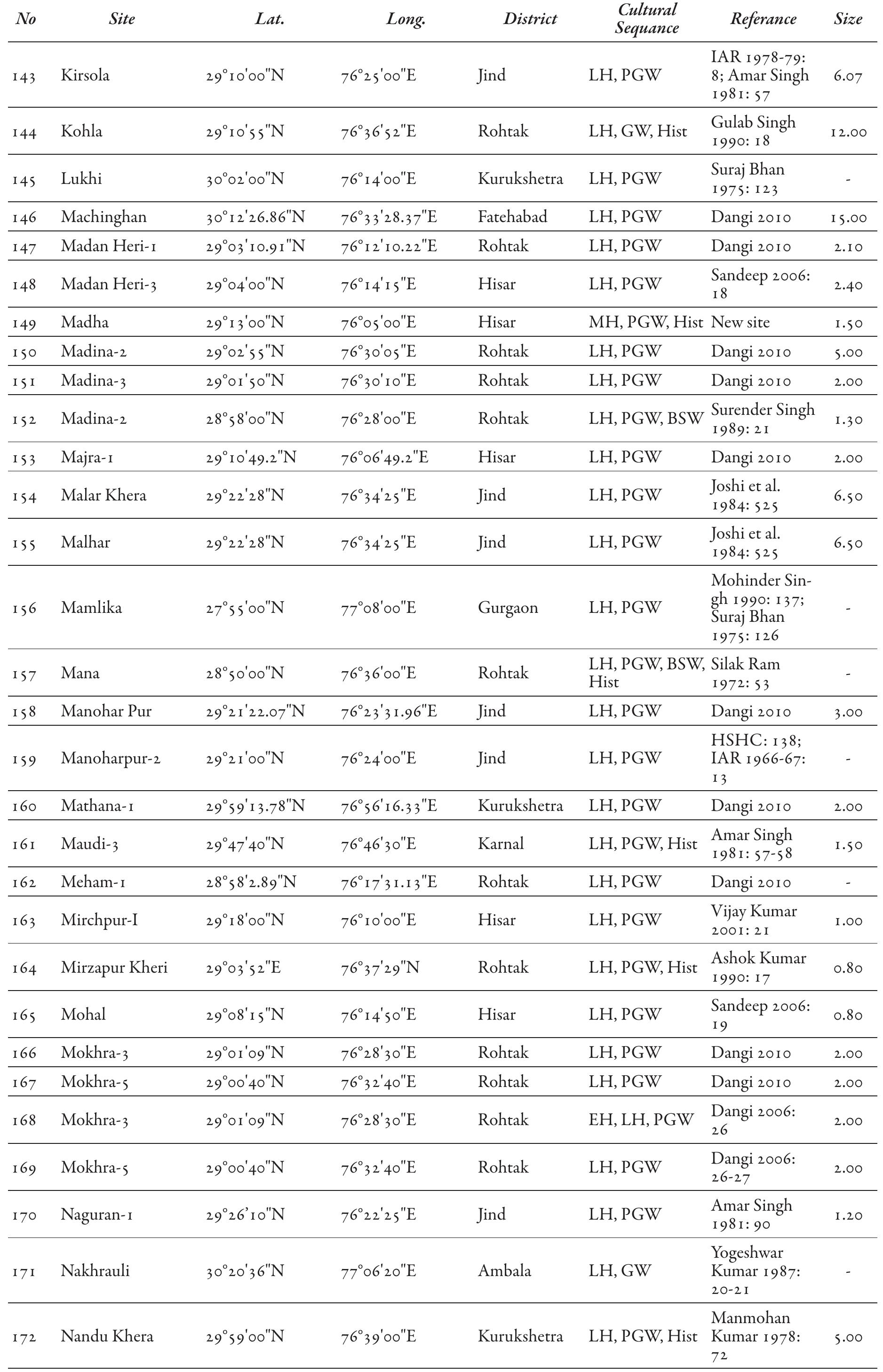

Appendix Late Harappan-PGW settlements in Ghaggar-Yamuna Divide Manmohan Kumar 259 PREFACE Report publishing is culmination of an archaeological expedition and it is a sheer wastage of money and efforts if an archaeological site goes unpublished. Wheeler has rightly said that every excavation is a destruction because the evidences once disturbed could not be put back at its original place. It makes it imperative for an archaeologist to record the excavations and excavated material properly. This is the first step which distinguishes the antiquarian from an archaeologist. By properly interpreting the recording, other archaeologists can reconstruct the whole deposits which are otherwise lost for posterity. If an archaeologist cannot perform this task "he should better leave archaeology and do something else". Keeping this in mind, this author started excavations at the ancient site of Madina and the purpose of the effort was to explore the link between the Late Harappan culture and Painted Grey Ware culture. Though a link had been first established at Bhagwanpura and subsequently at some other sites. But there remained some unanswered questions as to what was the nature of this link. Whether the authors of both the cultures stayed together despite their distinct cultural milieu and they adopted or shared each other's cultural traits. In the present excavations every care was taken to ensure that each and every antiquity and other features are properly recorded.

Key takeaways

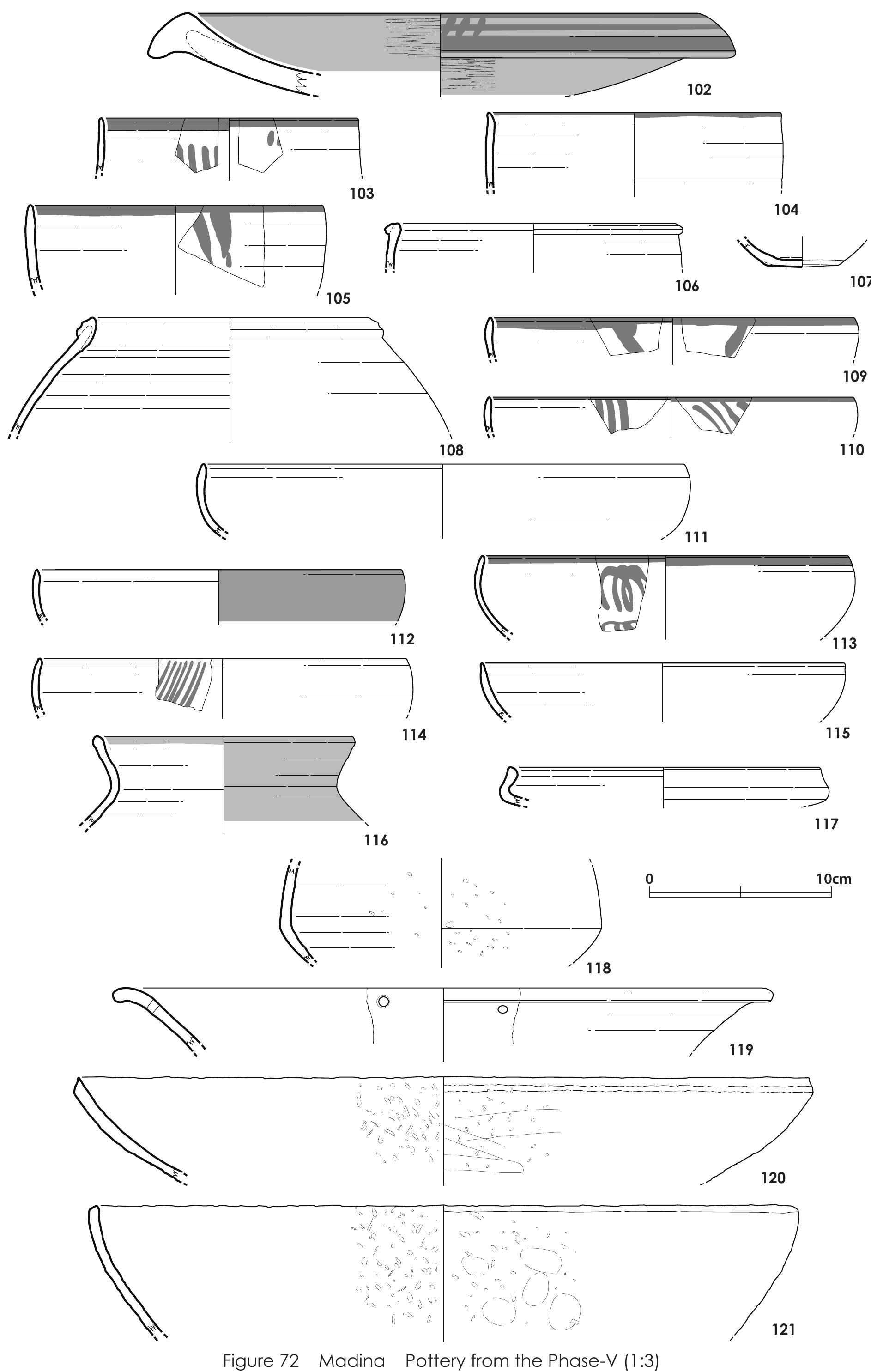

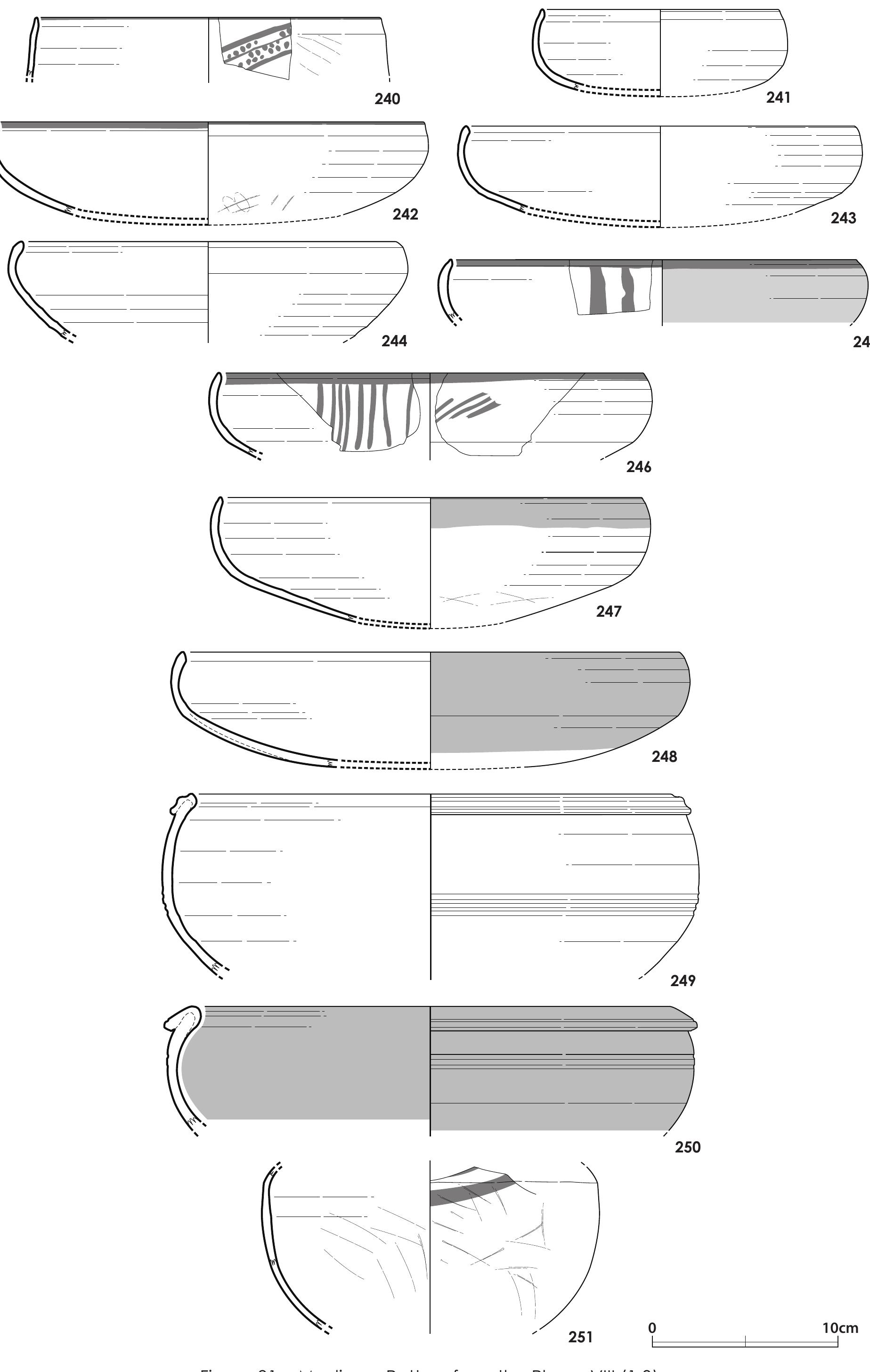

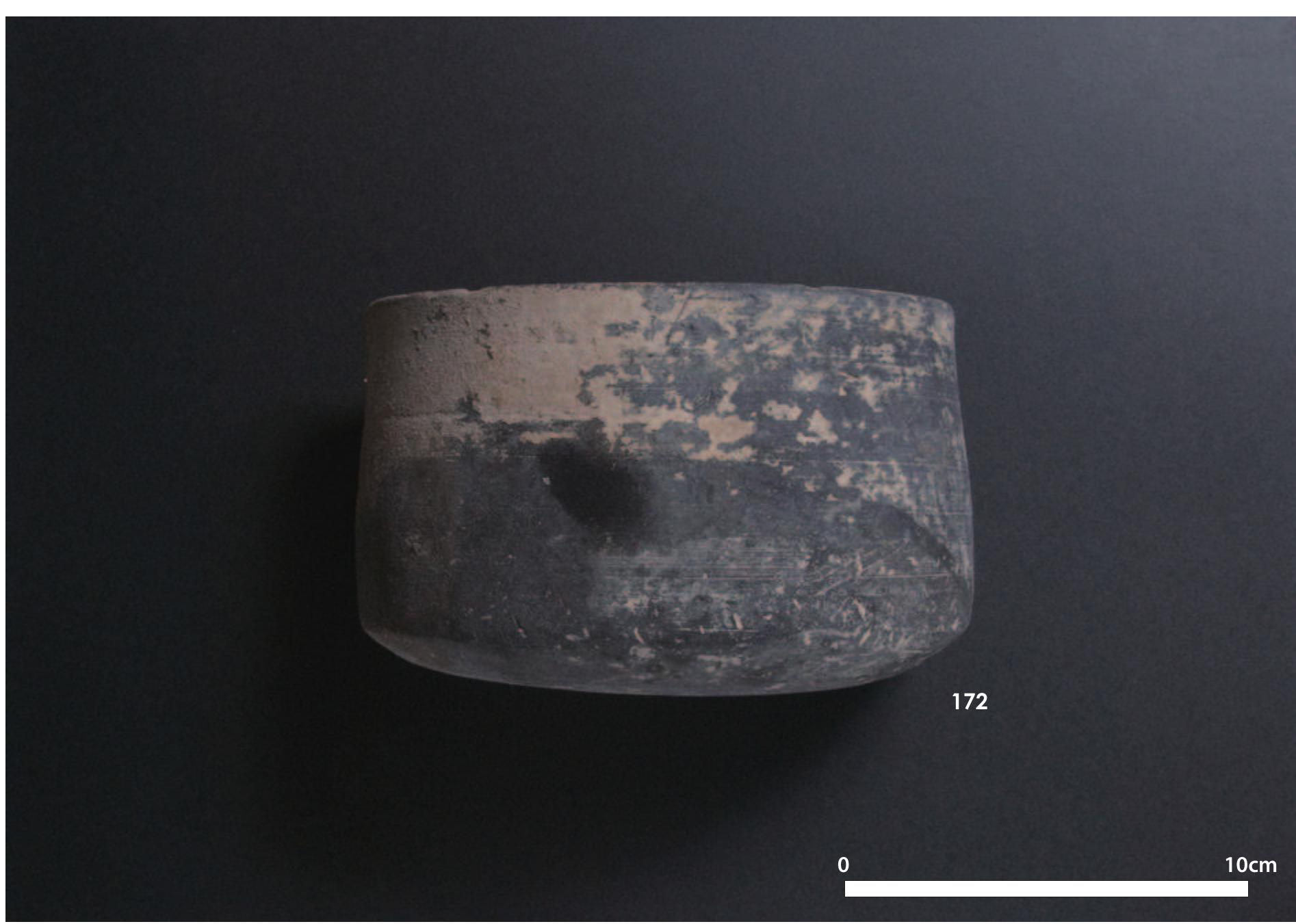

- This group represented by only two specimens of bowls is characterized by its colour distribution, i.e. a black colour on its internal surface and on the upper part of the external surface, and a red colour on the luting at the juncture between the neck and the body, and on their body.

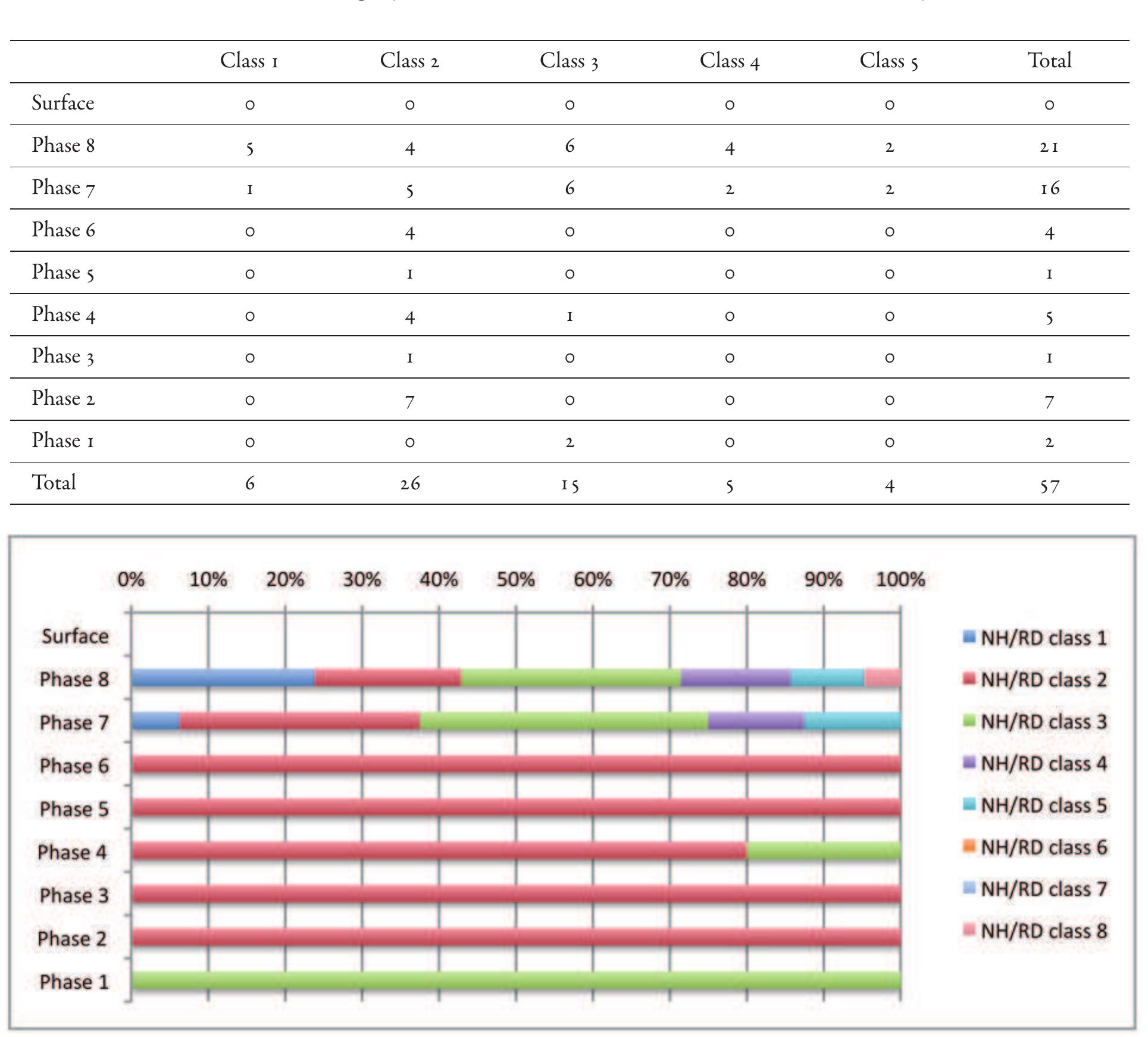

- Among the total specimens, 114 specimens represent bowls/ dishes and only one specimen a pot.

- As for the PGW, bowls are dominant through phases, For Bowl Type 3, only one specimen was found in the excavations (no.

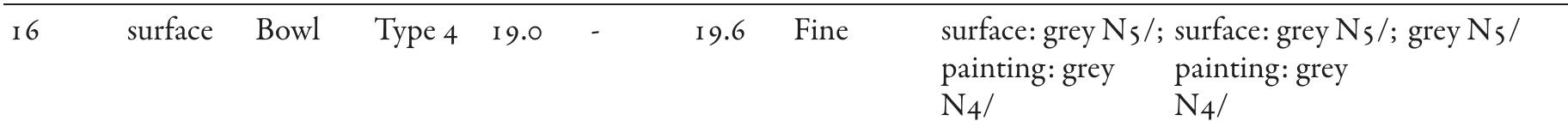

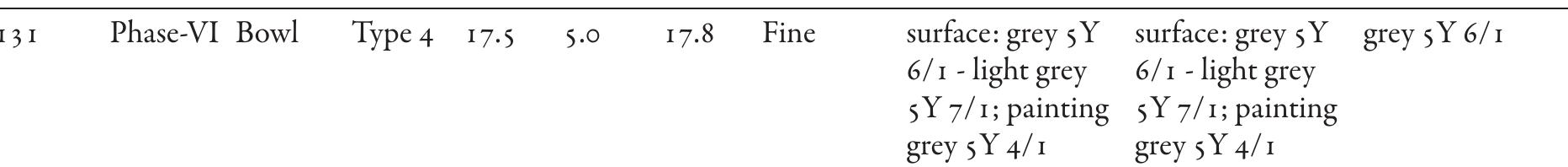

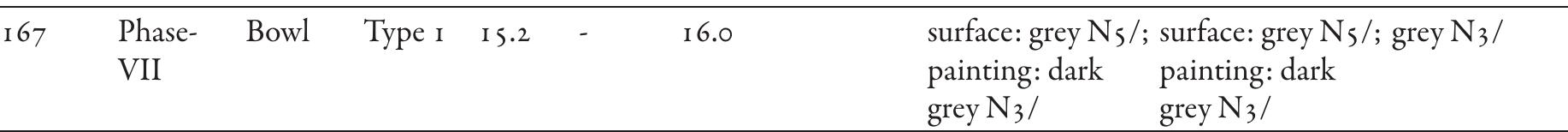

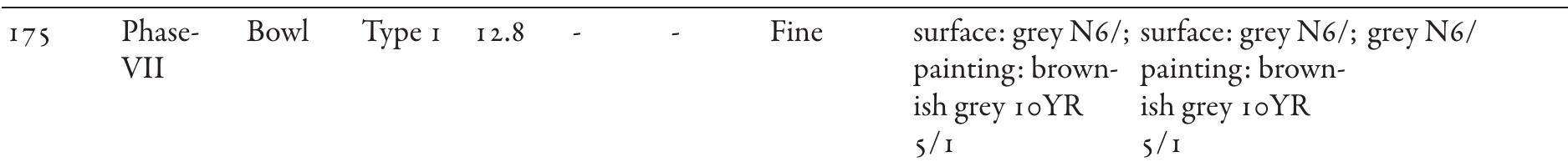

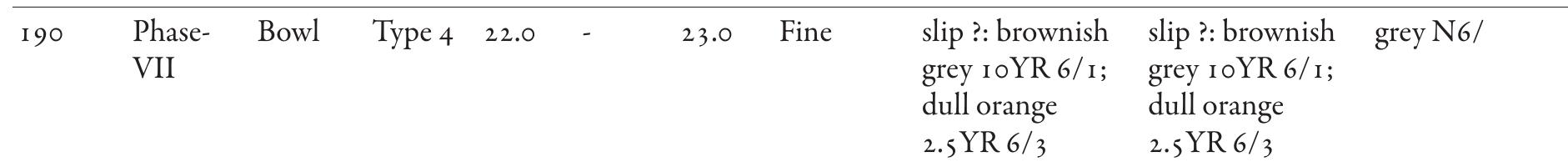

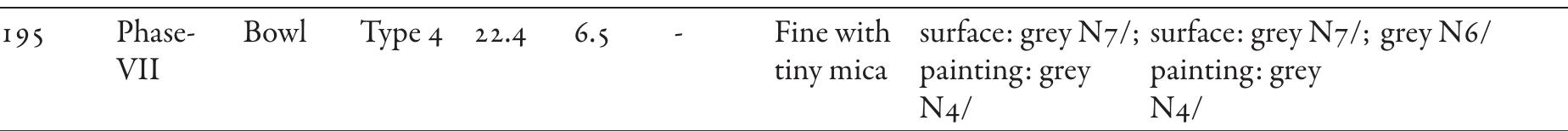

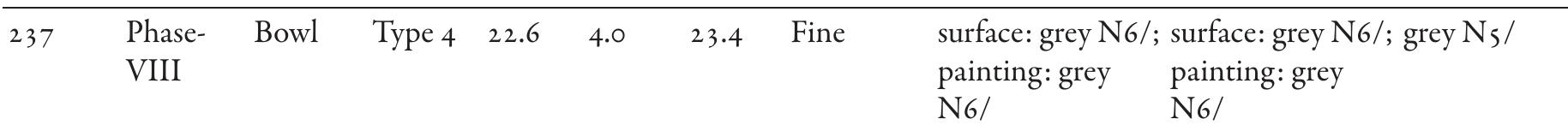

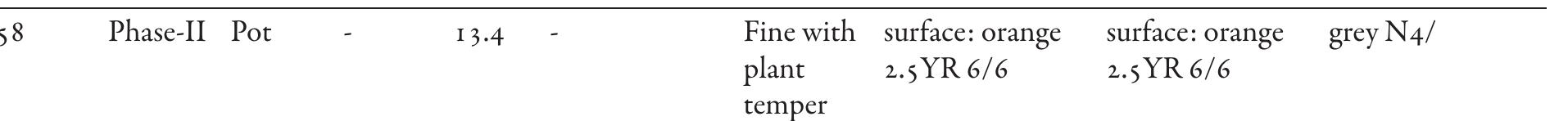

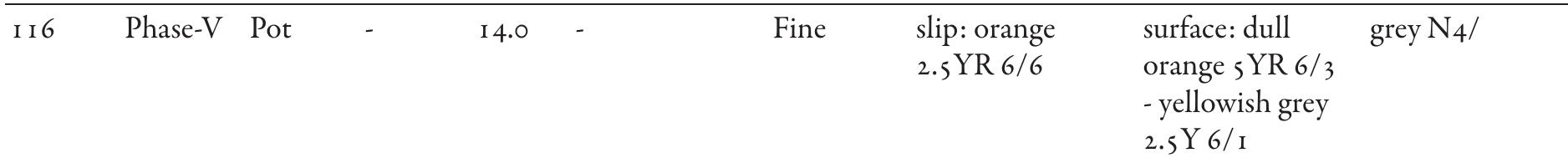

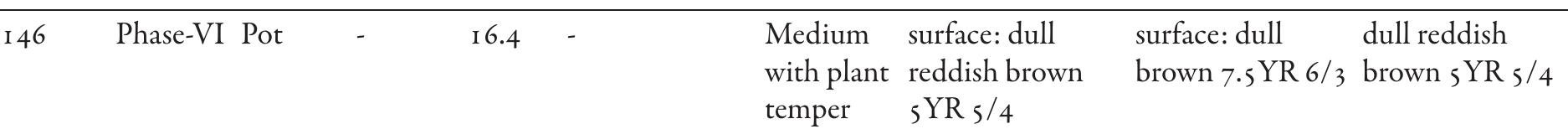

- Painted Grey ware (PGW) External colour Internal colour Section colour Dish, having convex sides and a pointed rim.

- colour Bowl, having a globular body and a beaded rim, The rim was modelled by luting technique.

Related papers

Indian Historical Review, 2003

Speaking Archaeologically Journal Volume III Issue I: Bhima Devi Edition, 2020

The Third Volume of the Speaking Archaeologically Journal is dedicated to our most ambitious project yet: The Bhima Devi Temple Project, that was undertaken by the Speaking Archaeologically Research Wing from October 2017 to December 2019. The Volume publishes various papers on the finds about the Gurjara Pratiharas in general and the Bhima Devi Temple of Pinjore in particular.

Man & Environment, 2013

Alamgirpur (29º 00.206'N; 77º 29.057'E) was earlier excavated by Y.D. Sharma in 1959, who confi rmed the Harappan affi liation of the site and revealed a four-fold cultural sequence with a break in between each period. However, later he (1989) revised the chronology, and mentioned that Period I had Harappan, Bara and some new but related wares. In view of this complication, a fresh limited excavation was conducted from April to June, 2008, by the Banaras Hindu University with the objectives to reconfi rm the cultural sequence on the basis of AMS dates, to study the faunal and fl oral remains, and to carry out palynological and geoarchaeological studies in order to understand the human response to the changing climatic conditions. However, establishing a chronology for the site was an essential component of this research. The new excavations at Alamgirpur carried out with a multidisciplinary approach revealed that the fi rst inhabitants of this site used Harappan (with a few Early Harappan and OCP) pottery, simple structures made with mud walls with thatched roofs based on wooden posts. Considering the material remains and the consistent AMS dates, the Harappan presence across the Yamuna River is now unquestionable. The date range of 2600 to 2200 B.C. (calibrated) has been proposed for the earliest level at Alamgirpur. On the basis of recent excavations and geoarchaeological study it has been suggested that there is no stratigraphic gap between Harappan and PGW levels. The study conducted on fuel exploitation, suggests that although the site was located in an open grassland environment where people had access to some wood resource, but forms of fuel other than wood was also exploited. Preliminary archaeobotanical analysis showed the presence of various cereals namely, barley, wheat and rice, and legumes such as vetch, wild/domesticated peas and mung bean, in addition to oil seeds suggesting agriculturebased subsistence economy of Harappa settlers at this site.

Dholavira Cuboid Chert 1.27 cm 1.25 cm 1.15 cm Good 4.02 g Dholavira Cuboid Copper 1.33 cm 1.24 cm 0.90 cm Erased 4.05 g Cat. no. Site Shape Material Length Height Width Diameter Condition Mass 69 Dholavira Hemisphere Limestone 3.18 cm 6.97 cm Good 182.76 g 70 Dholavira Truncated hemishphere Stone 3.16 cm 2.02 cm Erased 32.60 g Dholavira Truncated hemisphere Stone 1.22 cm 2.77 cm Good 17.21 g 72 Dholavira Dome-shaped Limestone 1.57 cm 0.62 cm Good 2.69 g 73 Dholavira Dome-shaped Stone 2.81 cm 2.80 cm Slightly chipped 29.88+x g One weight comes from Kuntasi (Cat. no. 1) from Period I (Tab. 7.2), a site located in the district of Rajkot on the right bank of the Phulki River. The site (2 hectares wide) was investigated by M. K. Dhavalikar of Deccan College, with M. R. Rawal and Y. M. Chitalwala, reporting two main phases of occupation: the first period must be considered the end of Mature Harappa (period I, 2200-1900 BCE), while the second period belongs to Late Harappa (1900-1700 BCE), mostly marked by a strong settlement contraction (Dhavalikar et al. 1996). The weight of Nagwada (Cat. no. 2) was found in Area XXIII, in A1 locus (Tab. 7.2). The site, one and a half acres in size, was excavated by the University of Baroda and is located only 3 kilometers from Nagwada. The excavations made it possible to identify two different archaeological phases: the IA and IB periods. The most archaic (IA) is characterized by some burials with pre-Harappan ceramics also known from Amri, Kot-Diji and Nal, while the IB period (the upper level has been dated to 2180 BCE by 14C analysis) shows many characteristics of Harappan type (inscribed terracotta sealing, agate weights, etched carnelian beads, flint blades, shell objects, beads of gold and semi-precious stones, etc.; see Hedge et al. 1988: 55-65; Sonawane and Ajithprasad 1994: 37-49). Two weights were found in Shikarpur (Cat. nos. 3-4), in the district of Kutch. The site was excavated between 1987 and 1990 by the Gujarat State Department of Archaeology by M. H. Raval allowing to recognize 3 meters of archaeological deposit of the Mature Harappan period, divided in 2 periods and 19 layers: 1-9 dated to the Mature Harappa and 10-19 to the Early Harappa period (Thomas et al. 1995: 34-41). Only one specimen (Cat. no. 5), well preserved, in agate and cuboid shape, comes from Bagasra. The Harappan site, known locally as Gola Dhoro, is about half a kilometre from the modern village in the Rajkot district, in the Gulf of Kutch. The site was explored by a joint mission of Deccan College, Pune and the Gujarat State Archaeology Department in the late 1980s. New investigations were subsequently carried out by the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History of the University of Baroda from 1995 onwards. The site has returned four main phases based on stratigraphic contexts, from the early stage of the Classic Harappa, along the so-called 'Anarta pottery' (Phase I), to Phase II with the construction of a new fortification and from Phase III (with a large quantity of Sorath Harappan pottery over the Classical Harappan) to the Phase IV, a Post-Mature Harappan occupation (Sonawane et al. 2003: 21-50; Bhan et al. 2004: 153-158). Much of our documentation (68 weights; Cat. nos. 6-73) comes from Dholavira in the Kutch district, excavated by R. S. Bisht (Archaeological Survey of India). It is one of the five largest Harappan centres in the Greater Indus. The excavations of Dholavira appear particularly important because they provide a reliable archaeological context of reference allowing timid considerations of a chronological nature (among the 68 weights of Dholavira, in fact, 47 have a well dated context). The site of Dholavira has been divided into 7 main periods showing the gradual rise, culmination and fall of the urban system of Harappan civilization. In details, Period IV (2500-2100 BCE) and V (2100-2000 BCE) have to be related to the Harappan mature period (in period V a general decline is attested), approximately corresponding to Harappa 3A-C, and Period VI (2000/1950-1800 BCE = Harappa IV) should be considered a late phase of Harappan cultural experiences; in this period the domestic buildings were laid out in a different way and, at the end of this stage, the site was abandoned (

Heritage:Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 1: 2013, Department of Archaeology, University of Kerla, Thiruvananthapuram

Village Seman is situated at a distance of about 8 km north of Meham town, a tehsil headquarter in Rohtak district of Haryana state. It is approachable by a metal road from Meham via Bhaini Surjan. It is about 120 km north west of New Delhi. There are seven proto historic sites in the revenue jurisdiction of this village including one cemetery, which is located about 1 km east of the village. Pottery recovered from the site belongs to classical Harappan phase. On the basis of location and material recovered from the site Seman 6 can be associated with Farmana 1. This site was extensively excavated in 2008 09 and the final report was published. In the present paper pottery recovered during the explorations is discussed which include some new type of pottery.

Related topics

Related papers

2024

Linkages of trade and culture between India and Myanmar, dating from the 1st millennium BCE, have been emphasized by several archaeologists. One of the significant set of artefacts that played a pivotal role in these processes of network is pottery. In this paper, the authors present the first ever comprehensive study of the physicochemical properties of potteries from important archaeological sites of India and Myanmar, chronoculturally dated between 1st century BCE and 13th century CE. Results showed an interesting correlation among samples, underlining regular interactions between India and Myanmar. This possibly resulted not only in the transport of pottery but also in the sharing of its manufacturing techniques. A strong correlation in the composition of different elements, their interplay and the resultant structural details of the pottery obtained from the two regions play a key role in solving this ever-debated puzzle.

Itihas Darpan, 2023

I am happy to release Indian Archaeology 1984-35-A Review and place it in the hands of readers and scholars. The publication of the Review has been somewhat in arrears. With this volume the gap has been further reduced. I hope we would be soon able to catch up with the arrears and make the publication uptodate.

In Bengali, the signifier abhijñān denotes ‘a token of recognition.’ The term also has embedded within it the notion of abhijñā or ‘memory’ and abhijña, or the ‘expert,’ the ‘wise,’ and the ‘experienced.’ These significations, overt and covert, are mobilized in this volume to pay tribute to an ‘amateur’ archaeologist, i.e., an archeologist not trained in the discipline but one whose amour or love for archaeology has rendered him abhijña as the ‘expert,’ the ‘wise,’ and the ‘experienced.’ As a collection of eighteen research papers on South Asian archaeology and art history of artefacts, contributed by twenty-two scholars from Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Italy and Germany, this volume of specially commissioned essays seeks to be a token of recognition that remembers and felicitates an expert, wise and experienced archeologist from Bangladesh, whose name is Abul Kalam Muhammad Zakariah.

Karsola is located (29° 09' 02.9" N, 76° 25'.36" E) in the Julana Tehsil of Jind district, Haryana. The ceramic industries/assemblage reported during initial explorations and excavation included PGW, Black Slipped Ware, and Stamped Ware of the Early Historic Period. A detail survey of the site revealed the presence of pottery belonging to three different cultural phases, including Late Harappan, PGW, and Early Historic (Kushana /Gupta). Present paper has attempted a precise study of PGW pottery assemblage at Karsola. Looking into the pottery assemblage, this paper has looked into the question of transition from Late Harappan to Painted Grey Ware cultural phase.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Akinori Uesugi

Akinori Uesugi Vivek Dangi

Vivek Dangi